Aral Sea

| Aral Sea | |

|---|---|

|

|

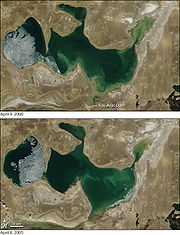

| 1989 and 2008 | |

| Location | |

| Lake type | Endorheic |

| Primary inflows | Amu Darya, Syr Darya |

| Basin countries | Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan |

| Surface area | 17,160 square kilometres (6,630 sq mi) (2004, three lakes) 28,687 square kilometres (11,076 sq mi) (1998, two lakes) 68,000 square kilometres (26,000 sq mi) (1960, one lake) |

| Max. depth | 102 m (335 ft) in 1989 42 m (138 ft) in 2008 (only northern part)[1] |

| Settlements | (Aral) |

The Aral Sea (Kazakh: Арал Теңізі Aral Teñizi; Uzbek: Orol Dengizi; Russian: Аральскοе Мοре Aral'skoye More; Tajik: Баҳри Арал Bahri Aral; Persian: دریاچه خوارزم Daryocha-i Khorazm) is a saline endorheic basin in Central Asia; it lies between Kazakhstan (Aktobe and Kyzylorda provinces) in the north and Karakalpakstan, an autonomous region of Uzbekistan, in the south. The name roughly translates as "Sea of Islands", referring to more than 1,500 islands that once dotted its waters.

Formerly one of the four largest lakes of the world with an area of 68,000 square kilometres (26,000 sq mi), the Aral Sea has been steadily shrinking since the 1960s after the rivers that fed it were diverted by Soviet Union irrigation projects. By 2007 it had declined to 10% of its original size, splitting into three lakes[2] – the North Aral Sea and the eastern and western basins of the once far larger South Aral Sea. By 2009, the south-eastern lake had disappeared and the south-western lake retreated to a thin strip at the extreme west of the former southern sea.[3] The maximum depth of the North Aral Sea is 42 metres (138 ft) (as of 2008).[1]

The region's once prosperous fishing industry has been virtually destroyed, bringing unemployment and economic hardship. The Aral Sea region is also heavily polluted, with consequent serious public health problems. The retreat of the sea has reportedly also caused local climate change, with summers becoming hotter and drier, and winters colder and longer.[4]

There is now an ongoing effort in Kazakhstan to save and replenish the North Aral Sea. As part of this effort, a dam project was completed in 2005; in 2008, the water level in this lake had risen by 12 metres (39 ft) from its lowest level in 2003.[1] Salinity has dropped, and fish are again found in sufficient numbers for some fishing to be viable. However, the outlook for the remnants of the South Aral Sea remains bleak. It has been called "one of the planet's worst environmental disasters".[5]

Contents |

History

Russian military presence on the Sea of Aral started in 1847, with the founding of Raimsk, which was soon renamed Aralsk, near the mouth of the Syr Darya. Soon, the Imperial Russian Navy started deploying its vessels on the sea. Owing to the Aral Sea basin not being connected to other bodies of water, the vessels had to be disassembled in Orenburg on the Ural River, shipped overland to Aralsk (presumably by a camel caravan), and then re-assembled. The first two ships, assembled in 1847, were the two-masted schooners named Nikolai and Mikhail. The former was a warship, the latter a merchant vessel meant to serve for the establishment of the fisheries on the great lake. In 1848, these two vessels surveyed the northern part of the sea. In the same year, a larger warship, the Constantine, was assembled as well. Commanded by Lt. Alexey Butakov (Алексей Бутаков), the Constantine completed the survey of the entire Aral Sea over the next two years.[6] The exiled Ukrainian poet and painter Taras Shevchenko participated in the expedition, and painted a number of sketches of the Aral Sea coast.[7]

For the navigation of 1851, two newly built steamers arrived from Sweden, again via caravan from Orenburg. As the geological surveys had found no coal deposits in the area, the Military Governor-General of Orenburg Vasily Perovsky ordered "as large as possible supply" of saxaul (a desert shrub, akin to the creosote bush) to be collected in Aralsk for use by the new steamers. Unfortunately, saxaul wood did not turn out a very suitable fuel, and in the later years the Aral Flotilla was provisioned, at substantial cost, by Donets coal.[6]

Shrinkage

History

In 1918,[8] the Soviet government decided that the two rivers that fed the Aral Sea, the Amu Darya in the south and the Syr Darya in the northeast, would be diverted to irrigate the desert, in order to attempt to grow rice, melons, cereals, and cotton. 30 million roubles were spent on the scheme, and Lenin said that "Irrigation will do more than anything else to revive the area and regenerate it, bury the past and make the transition to socialism more certain".[8]

This was part of the Soviet plan for cotton, or "white gold", to become a major export. This did eventually end up becoming the case, and today Uzbekistan is one of the world's largest exporters of cotton.[9]

Irrigation canals

The construction of irrigation canals began on a large scale in the 1940s. Many of the canals were poorly built, allowing water to leak or evaporate. From the Qaraqum Canal, the largest in Central Asia, perhaps 30 to 75% of the water went to waste. Today only 12% of Uzbekistan's irrigation canal length is waterproofed.

By 1960, between 20 and 60 cubic kilometres (4.8 and 14 cu mi) of water were going each year to the land instead of the sea. Most of the sea's water supply had been diverted, and in the 1960s the Aral Sea began to shrink. From 1961 to 1970, the Aral's sea level fell at an average of 20 cm (7.9 in) a year; in the 1970s, the average rate nearly tripled to 50–60 centimetres (20–24 in) per year, and by the 1980s it continued to drop, now with a mean of 80–90 centimetres (31–35 in) each year. The rate of water usage for irrigation continued to increase: the amount of water taken from the rivers doubled between 1960 and 2000, and cotton production nearly doubled in the same period.

The disappearance of the lake was no surprise to the Soviets; they expected it to happen long before. As early as in 1964, Aleksandr Asarin at the Hydroproject Institute pointed out that the lake was doomed, explaining "It was part of the five-year plans, approved by the council of ministers and the Politburo. Nobody on a lower level would dare to say a word contradicting those plans, even if it was the fate of the Aral Sea."[10]

The reaction to the predictions varied. Some Soviet experts apparently considered the Aral to be "nature's error", and a Soviet engineer said in 1968 that "it is obvious to everyone that the evaporation of the Aral Sea is inevitable."[11] On the other hand, starting in the 1960s, a large scale project was proposed to redirect part of the flow of the rivers of the Ob basin to Central Asia over a gigantic canal system. Refilling of the Aral Sea was considered as one of the project's main goals. However, due to its staggering costs and the negative public opinion in Russia proper, the federal authorities abandoned the project by 1986.[12]

From 1960 to 1998, the sea's surface area shrank by approximately 60%, and its volume by 80%. In 1960, the Aral Sea had been the world's fourth-largest lake, with an area of approximately 68,000 square kilometres (26,000 sq mi) and a volume of 1,100 cubic kilometres (260 cu mi); by 1998, it had dropped to 28,687 square kilometres (11,076 sq mi), and eighth-largest. The amount of water it has lost is the equivalent of completely draining Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. Over the same time period its salinity increased from about 10 g/L to about 45 g/L.

Aral Sea from space, August 1985 |

_from_STS.jpg) Aral Sea from space, 1997 |

Aral Sea from space, August 2009 |

In 1987, the continuing shrinkage split the lake into two separate bodies of water, the North Aral Sea (the Lesser Sea, or Small Aral Sea) and the South Aral Sea (the Greater Sea, or Large Aral Sea).

As of summer 2003[update], the South Aral Sea was vanishing faster than predicted. In the deepest parts of the sea, the bottom waters are saltier than the top, and not mixing. Thus, only the top of the sea is heated in the summer, and it evaporates faster than would otherwise be expected. In 2003, the South Aral further divided into eastern and western basins.

As of 2004, the Aral Sea's surface area was only 17,160 km2 (6,630 sq mi), 25% of its original size, and a nearly fivefold increase in salinity had killed most of its natural flora and fauna. By 2007 the sea's area had further shrunk to 10% of its original size, and the salinity of the remains of the South Aral had increased to levels in excess of 100 g/L.[2] (By comparison, the salinity of ordinary seawater is typically around 35 g/L; the Dead Sea's salinity varies between 300 and 350 g/L.) The decline of the North Aral has now been partially reversed following construction of a dam (see below) but the remnants of the South Aral continue to disappear and its drastic shrinkage has created the Aralkum, a desert on the former lakebed.

Even the recently discovered inflow of water discharge from underground into the Aral Sea will not in itself be able to stop the desiccation. This inflow of about 4 cubic kilometres (0.96 cu mi) per year is larger than previously estimated. This groundwater originates in the Pamirs and Tian Shan mountains and finds its way through geological layers to a fracture zone at the bottom of the Aral.

Impact on environment, economy and public health

The ecosystem of the Aral Sea and the river deltas feeding into it has been nearly destroyed, not least because of the much higher salinity. The receding sea has left huge plains covered with salt and toxic chemicals – the results of weapons testing, industrial projects, pesticides and fertilizer runoff – which are picked up and carried away by the wind as toxic dust and spread to the surrounding area. The land around the Aral Sea is heavily polluted and the people living in the area are suffering from a lack of fresh water and health problems, including high rates of certain forms of cancer and lung diseases. Respiratory illnesses including tuberculosis (most of which is drug resistant) and cancer, digestive disorders, anaemia, and infectious diseases are common ailments in the region. Liver, kidney and eye problems can also be attributed to the toxic dust storms. Health concerns associated with the region are a cause for an unusually high fatality rate amongst vulnerable parts of the population. There is a high child mortality rate of 75 in every 1,000 newborns and maternity death of 12 in every 1,000 women.[13] Crops in the region are destroyed by salt being deposited onto the land. Vast salt plains exposed by the shrinking Aral have produced dust storms, making regional winters colder and summers hotter.[14][15][16][17]

The Aral Sea fishing industry, which in its heyday had employed some 40,000 and reportedly produced one-sixth of the Soviet Union's entire fish catch, has been decimated, and former fishing towns along the original shores have become ship graveyards. The town of Moynaq in Uzbekistan had a thriving harbor and fishing industry that employed approximately 30,000 people [18]; now it lies miles from the shore. Fishing boats lie scattered on the dry land that was once covered by water; many have been there for 20 years. The only significant fishing company left in the area has its fish shipped from the Baltic Sea, thousands of kilometers away.

Also destroyed is the muskrat trapping industry in the deltas of Amu Darya and Syr Darya, which used to yield as much as 500,000 muskrat pelts a year.[10]

Possible environmental solutions

Many different solutions to the different problems have been suggested over the years, varying in feasibility and cost, including the following:

- Improving the quality of irrigation canals;

- Installing desalination plants;

- Charging farmers to use the water from the rivers;

- Using alternative cotton species that require less water;[19]

- Using fewer chemicals on the cotton;

- Moving farming away from cotton;

- Installing dams to fill the Aral Sea;

- Redirecting water from the Volga, Ob and Irtysh rivers. This would restore the Aral Sea to its former size in 20–30 years at a cost of US$30–50 billion;[20]

- Pumping sea water into the Aral Sea from the Caspian Sea via a pipeline, and diluting with freshwater from local catchment areas.[21]

In January 1994, the countries of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan signed a deal to pledge 1% of their budgets to helping the sea recover.

In March 2000 UNESCO presented their Water-related vision for the Aral Sea basin for the year 2025 at the second World Water Forum in The Hague. This document was criticized for setting unrealistic goals, and also for giving insufficient attention to the interests of the area immediately around the former lakesite, implicitly giving up on the Aral Sea and the people living on the Uzbek side of the lake.[22]

By 2006, the World Bank's restoration projects, especially in the North Aral, were giving rise to some unexpected, tentative relief in what had been an extremely pessimistic picture.[23]

North Aral Sea restoration work

Work is being done to restore in part the North Aral Sea. Irrigation works on the Syr Darya have been repaired and improved to increase its water flow, and in October 2003, the Kazakh government announced a plan to build Dike Kokaral, a concrete dam separating the two halves of the Aral Sea. Work on this dam was completed in August 2005; since then the water level of the North Aral has risen, and its salinity has decreased. As of 2006, some recovery of sea level has been recorded, sooner than expected.[24] "The dam has caused the small Aral's sea level to rise swiftly to 38 m (125 ft), from a low of less than 30 m (98 ft), with 42 m (138 ft) considered the level of viability."[25] Economically significant stocks of fish have returned, and observers who had written off the North Aral Sea as an environmental disaster were surprised by unexpected reports that in 2006 its returning waters were already partly reviving the fishing industry and producing catches for export as far as Ukraine. The restoration reportedly gave rise to long absent rain clouds and possible microclimate changes, bringing tentative hope to an agricultural sector swallowed by a regional dustbowl, and some expansion of the shrunken sea.[26] "The sea, which had receded almost 100 km (62 mi) south of the port-city of Aral, is now a mere 25 km (16 mi) away." The Kazakh Foreign Ministry stated that “The North Aral Sea's surface increased from 2,550 square kilometers (985 square miles) in 2003 to 3,300 square kilometers (1,275 square miles) in 2008. The sea's depth increased from 30 meters (98 ft) in 2003 to 42 meters (138 ft) in 2008.” [1] Now, a second dam is to be built based on a World Bank loan to Kazakhstan, with the start of construction slated for 2009, to further expand the shrunken Northern Aral,[27] eventually reducing the distance to Aralsk to only 6 km (3.7 mi). Then, it was planned to build a canal spanning the last 6 km, to reconnect the withered former port of Aralsk with the sea.[28]

Future of South Aral Sea

The South Aral Sea, which lies in poorer Uzbekistan, was largely abandoned to its fate. Projects in the North Aral at first seemed to bring glimmers of hope to the South as well: "In addition to restoring water levels in the Northern Sea, a sluice in the dike is periodically opened, allowing excess water to flow into the largely dried-up Southern Aral Sea."[29] Discussions had been held on recreating a channel between the somewhat improved North and the desiccated South, along with uncertain wetland restoration plans throughout the region, but political will is lacking.[24] Uzbekistan shows no interest in abandoning the Amu Darya river as an abundant source of cotton irrigation, and instead is moving toward oil exploration in the drying South Aral seabed.[28] Attempts to mitigate the effects of desertification include planting vegetation in the newly exposed seabed.

Institutional bodies

The Interstate Commission for Water Coordination of Central Asia (ICWC) was formed on February 18, 1992 formally uniting five Central Asian countries in the hopes of solving environmental as well as socio-economic problems in the Aral Sea region. These five states are the Republic of Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, the Republic of Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and the Republic of Uzbekistan. The River Basin Organizations (the BVO’s) of the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers were institutions called upon by the ICWC to help manage water resources. According to the ICWC the main objectives of the body are:

- River basin management;

- Non-conflict water allocation;

- Organization of water conservation on transboundary water courses;

- Interaction with hydro meteorological services of the countries on flow forecast and account;

- Introduction of automation into head structures;

- Regular work on ICWC and its bodies activity advancement;

- Interstate Agreements preparation;

- International relations;

- Scientific researches;

- Training.

The International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea (IFAS) was developed on March 23, 1993 by the ICWC to raise funds for the projects under Aral Sea Basin Programs. The IFAS was meant to finance programs to save the sea and improve on environmental issues associated with the basin’s drying. This program has had some success with joint summits of the countries involved and finding funding from the World Bank, to implement projects; however, it faces many challenges, such as enforcement and slowing progress. [30]

Bioweapons facility on Vozrozhdeniya Island

In 1948, a top-secret Soviet bioweapons laboratory was established on the island in the center of the Aral Sea which is now disputed territory between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. The exact history, functions and current status of this facility have not yet been disclosed. The base was abandoned in 1992 following the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Scientific expeditions proved that this had been a site for production, testing and later dumping of pathogenic weapons. In 2002, through a project organized by the United States and with Uzbekistan's assistance, 10 anthrax burial sites were decontaminated. According to the Kazakh Scientific Center for Quarantine and Zoonotic Infections, all burial sites of anthrax were decontaminated.[31]

Oil and gas exploration

Ergash Shaismatov, the Deputy Prime Minister of Uzbekistan, announced on August 30, 2006, that the Uzbek government and an international consortium consisting of state-run Uzbekneftegaz, LUKoil Overseas, Petronas, Korea National Oil Corporation, and China National Petroleum Corporation signed a production sharing agreement to explore and develop oil and gas fields in the Aral Sea, saying, "The Aral Sea is largely unknown, but it holds a lot of promise in terms of finding oil and gas. There is risk, of course, but we believe in the success of this unique project." The consortium was created in September 2005.[32]

As of June 1, 2010, 500,000 cubic meters of gas had been extracted from the region at a depth of 3km.[33]

In popular culture

In movies

The tragedy of Aral coast was portrayed in the 1989 film, Psy ("Dogs"), by Soviet director, Dmitriy Svetozarov.[34] The film was shot on location in the actual ghost town, showing scenes of abandoned buildings and scattered vessels.

Also in 1989 Kazakh director Rashid Nugmanov used the barren landscape around the Aral Sea for his movie The Needle.

In 1998 Dutch director Ben van Lieshout shot his film De Verstekeling ("The Stowaway") partly on the dry sea shore near Muynak.

In 1999 German filmmaker Joachim Tschirner produced the documentary Der Aralsee for the German channel Arte.

In 2000 the MirrorMundo foundation produced a documentary film called Delta Blues about the problems arising from the drying up of the sea.[35]

The 2004 film "Rebirth Island" (Russian: Остров Возрождения; Kazakh: Каладан келген кыз), about the life of Kazakh poet Zharaskan Abdirash, took place near the Aral Sea.

In June 2007 BBC World broadcast a documentary called Back From The Brink? made by Borna Alikhani and Guy Creasey that showed some of the changes in the region since the introduction of the Aklak Dam.

The TV series Long Way Round, originally shown on TV in the UK, featured a short segment in episode #3 on the area.

In literature

Oxus, forgetting the bright speed he had

In his high mountain-cradle in Pamere,

A foiled circuitous wanderer: — till at last

The longed-for dash of waves is heard, and wide

His luminous home of waters opens, bright

And tranquil, from whose floor the new-bathed stars

Emerge, and shine upon the Aral Sea– Matthew Arnold, Sohrab and Rustum

See also

- North Aral Sea

- South Aral Sea

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "The Kazakh Miracle: Recovery of the North Aral Sea". Environment News Service. 2008-08-01. http://www.ens-newswire.com/ens/aug2008/2008-08-01-01.asp. Retrieved 2010-03-22.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Philip Micklin; Nikolay V. Aladin (March 2008). "Reclaiming the Aral Sea". Scientific American. http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=reclaiming-the-aral-sea&sc=rss. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ Satellite image, August 16, 2009 (click on "2009" link)

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey (2007-05-01). "Earthshots: Aral Sea". U.S. Department of the Interior. http://earthshots.usgs.gov/Aral/Aral. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ Daily Telegraph (2010-04-05). "Aral Sea 'one of the planet's worst environmental disasters'". http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/earthnews/7554679/Aral-Sea-one-of-the-planets-worst-environmental-disasters.html. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Michell, John; Valikhanov, Chokan Chingisovich; Venyukov, Mikhail Ivanovich (1865). The Russians in Central Asia: their occupation of the Kirghiz steppe and the line of the Syr-Daria : their political relations with Khiva, Bokhara, and Kokan : also descriptions of Chinese Turkestan and Dzungaria; by Capt. Valikhanof, M. Veniukof and others. Translated by John Michell, Robert Michell. E. Stanford. pp. 324–329. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023159621.

- ↑ Rich, David Alan (1998). The Tsar's colonels: professionalism, strategy, and subversion in late Imperial Russia. Harvard University Press. p. 247. ISBN 0674911113. http://books.google.com/?id=lF42jb5Fg4cC.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Soviet cotton threatens a region's sea - and its children". New Scientist. 18 November 1989. http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg12416910.800-soviet-cotton-threatens-a-regions-sea--and-its-children.html. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ↑ USDA-Foreign Agriculture Service (2008). "Cotton Production Ranking". National Cotton Council of America. http://www.cotton.org/econ/cropinfo/cropdata/rankings.cfm. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Michael Wines (2002-12-09). "Grand Soviet Scheme for Sharing Water in Central Asia Is Foundering". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D03E4DA1F3BF93AA35751C1A9649C8B63&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ↑ Bissell, Tom (2002). Eternal Winter: Lessons of the Aral Sea Disaster. Harper's. pp. 41–56.

- ↑ Glantz, Michael H. (1999). Creeping Environmental Problems and Sustainable Development in the Aral Sea.... Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 174. ISBN 0521620864. http://books.google.com/?id=2YXnBxZg7c4C. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ <http://enrin.grida.no/aral/aralsea/english/arsea/arsea.htm>

- ↑ Godwin O. P. Obasi, Challenges and Opportunities in Water Resource Management, World Meteorological Organization (Lecture at the 93rd Annual Meeting of the American Meteorological Society, February 11, 2003)

- ↑ "Aral Sea". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2007. http://concise.britannica.com/ebc/article-9355673/Aral-Sea. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ Dust Storm, Aral Sea, NASA Earth Observatory image, June 30, 2001

- ↑ Whish-Wilson, Phillip (2002). "The Aral Sea environmental health crisis" (PDF). Journal of Rural and Remote Environmental Health 1 (2): 30. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.35.031306.140120. http://www.jcu.edu.au/jrtph/vol/v01whish.pdf. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ http://www.unicef.org/ceecis/reallives_3304.html

- ↑ "Water Actions - Uzbekistan". ADB.org. http://www.adb.org/water/actions/uzb/farmers-scientists.asp. Retrieved 2010-04-04.

- ↑ Ed Ring (2004-09-27). "Release the Rivers: Let the Volga & Ob Refill the Aral Sea". Ecoworld. http://www.ecoworld.com/Home/Articles2.cfm?TID=354. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ "Aral Sea Refill: Seawater Importation Macroproject". The Internet Encyclopedia of Science. 2008-06-29. http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/A/Aral_Sea_refill.html. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ "(Nederland) - UNESCO promotes unsustainable development in Central Asia". Indymedia NL. http://indymedia.nl/nl/2007/02/42459.shtml. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ "A Witch's Brew". BBC News. July 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/documentary_archive/5218248.stm. Retrieved 2008-05-17. (MP3) A Witch's Brew, Part Two: Regeneration. [Video]. BBC News. July 2006. http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/rmhttp://downloadtrial/worldservice/documentaryarchive/documentaryarchive_20060727-1000_40_st.mp3. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Ilan Greenberg (2006-04-07). "A vanished Sea Reclaims its form in Central Asia". The International Herald Tribune. http://www.iht.com/articles/2006/04/05/news/sea.php. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ Ilan Greenberg (2006-04-06). "As a Sea Rises, So Do Hopes for Fish, Jobs and Riches". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/06/world/asia/06aral.html. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ↑ "Miraculous Catch in Kazakhstan's Northern Aral Sea". The World Bank. June 2006. http://go.worldbank.org/J4UFHM4SQ1. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ "North Aral Sea Recovery". The Earth Observatory. NASA. 2007. http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Newsroom/NewImages/images.php3?img_id=17634. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Martin Fletcher (2007-06-23). "The return of the sea". The Times (London). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article1975079.ece. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ "Saving a Corner of the Aral Sea". The World Bank. 2005-09-01. http://go.worldbank.org/IE3PGWPVJ0. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ "IFAS". WaterWiki.net. http://waterwiki.net/index.php/IFAS_-_International_Fund_for_Saving_the_Aral_Sea. Retrieved 2010-04-04.

- ↑ Khabar Television/BBC Monitoring (2002-11-20). "Kazakhstan: Vozrozhdeniya Anthrax Burial Sites Destroyed". Global Security Newswire (Nuclear Threat Initiative). http://www.nti.org/d_newswire/issues/newswires/2002_11_20.html. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ Uzbekistan, intl consortium ink deal on exploring Aral Sea ITAR-Tass

- ↑ [1] Registan.net

- ↑ "www.kinoexpert.ru". www.kinoexpert.ru. http://www.kinoexpert.ru/index.asp?comm=4&num=5583. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ "Delta Blues (in a land of cotton)". YouTube. 2008-11-05. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0465vGRWhQE. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

Further reading

- Micklin, Philip (2007). "The Aral Sea Disaster". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 35 (4): 47–72. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.35.031306.140120. http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev.earth.35.031306.140120. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- Bissell, Tom (April 2002). "Eternal Winter: Lessons of the Aral Sea Disaster". Harper's: pp. 41–56. http://harpers.org/archive/2002/04/0079135. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- Bissell, Tom (2004). Chasing The Sea: Lost Among the Ghosts of Empire in Central Asia. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 9780375727542.

- Ellis, William S (February 1990). "A Soviet Sea Lies Dying". National Geographic: pp. 73–93.

- Ferguson, Rob (2003). The Devil and the Disappearing Sea. Vancouver: Raincoast Books. ISBN 1551925990.

- Kasperson, Jeanne; Kasperson, Roger; Turner, B.L (1995). The Aral Sea Basin: A Man-Made Environmental Catastrophe. Dordrecht; Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 92. ISBN 9280808486.

- Bendhun, François; Renard, Philippe (2004). "Indirect estimation of groundwater inflows into the Aral sea via a coupled water and salt mass balance model". Journal of Marine Systems 47 (1-4): 35–50. doi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2003.12.007. http://www1.unine.ch/chyn/php/publica_detail.php?id=560. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- Sirjacobs, Damien; Grégoire, Marilaure; Delhez, Eric; Nihoul, JCJ (2004). "Influence of the Aral Sea negative water balance on its seasonal circulation patterns: use of a 3D hydrodynamic model". Journal of Marine Systems 47 (1-4): 51–66. doi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2003.12.008. http://hdl.handle.net/2268/2793.

External links

- "Aral Sea Foundation". http://www.aralsea.org/. Retrieved April 2010.

- "The Aral Sea Crisis". Union for Defence of the Aral Sea and Amudarya river (UDASA). http://www.udasa.org/. Retrieved April 2010.

- "Water-related vision for the Aral Sea basin for the year 2025" (in English/Russian). UNESCO. March 2000. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001262/126259mo.pdf. Retrieved April 2010.

- MirrorMundo (February 2007). "UNESCO promotes unsustainable development in Central Asia". Indymedia. http://indymedia.nl/nl/2007/02/42459.shtml. Retrieved April 2010.

- "Syr Darya Control & Northern Aral Sea Phase I Project". World Bank Group - Kazakhstan. December 2006. http://www.worldbank.org.kz/external/projects/main?pagePK=64283627&piPK=73230&theSitePK=361869&menuPK=361902&Projectid=P046045. Retrieved April 2010.

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||